Distributed Denial-of-Service¶

Written by Taylor, Edited by Esteban and Morgan.

Introduction¶

Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) is a type of Denial-of-Service when an attacker overloads a server with requests and it stops being able to process them. However, DDoS is harder to prevent and stop, because instead of one computer attacking a target, an attacker will take over many computers to attack a target by sending multiple messages or connection requests to it. Furthermore, it is more difficult to distinguish these attacks from real requests due to certain circumstances such as a spike in a website's popularity [Rou]. The victim computer, website, or network source may be significantly slower or shut down denying real users of the service. This is a more advanced security breach than an attack from a single host or IP address where they can be blocked easily with a firewall [Kar].

This image depicts a typical DDoS attack [Dsa].

In a DDoS attack, an attacker exploits a weakness of a computer system and becomes the DDoS master. The DDoS master then finds other weak systems and gains control using malware or bypassing their security. The computers that are under the control of the attacker are called zombies or bots. There can be any number of zombie computers from ten to thousands, or even millions that make up a botnet [Rou].

Past DDoS Attack Examples¶

Past Large Botnets¶

The ability for hackers to gain control of large botnets gives them the possibility to do cybercriminal activity, send billions of spam emails, and complete large DDoS attacks. The security industry estimates that over time, botnets have resulted in more than $110 billion in losses to victims globally [Zet].

Although there have been many botnets, here are a few noteworthy ones:

- Grum - From 2008 to 2012, it became responsible for up to 26% of the world's spam traffic. In 2010, it was capable of emitting 39.9 billion messages a day, making it the largest botnet at the time.

- ZeroAccess - Estimated to have controlled 1.9 million computers around the world, focusing on click fraud and bitcoin mining. It was reported to be consuming enough energy to power 111,000 homes per day from all of its infected computers.

- Windigo - Discovered in 2014 after running undetected for three years. It infected 10,000 Linux servers and sent 35 million spam emails a day, infecting 500,000 computers. It had different forms of malware depending on the operating system of the device receiving it.

- Conficker - At its peak in 2009, it was estimated to have infected 15 million computers, but the total number of machines under the botnet control totaled between 3 and 4 million.

- Srizbi - Only active for about a year, but was responsible for 60% of spam worldwide and sent 60 billion emails every day from 2007 to 2008. When it was taken offline, spam volume worldwide dropped by 75%.

- Bredolab - Hijacked more than 30 million machines. Georgy Avanesov developed it in 2009 to collect bank account passwords but also earned about $125,000 a month from renting out access of his botnet to other criminals to spread malware and conduct DDoS attacks [Tho].

Large DDoS Attack on Dyn¶

On October 21, 2016, the DNS provider, Dyn, was a victim of a DDoS attack. This impacted users from using popular websites that are Dyn customers including Twitter, Reddit, Twitter, Spotify, and Netflix. The attacker used a Mirai botnet, a network of infected Internet of Things devices such as security cameras and DVR players that have poor security. It is estimated that there were 100,000 infected devices that caused the attack with a magnitude of 1.2 Tbps.

"Attacking a DNS or a content delivery provider such as Dyn or Akamai in this manner gives hackers the ability to interrupt many more companies than they could by directly attacking corporate servers, because several companies shared Dyn's network." -Spectrum magazine

This attack came in three phases throughout the course of the day. Since it was difficult to distinguish legitimate traffic from attack traffic, it was very difficult to mitigate. Furthermore, legitimate retry activity caused 10 to 20 times more traffic volume from many IP addresses around the world.

Dyn's Engineering and Operations teams worked hard to mitigate the attack and some of their techniques included traffic-shaping incoming traffic, applications of internal filtering, and deployment of scrubbing services [Hil]

Involving the FBI¶

In April 2011, the FBI obtained a court order to seize control of a server used to command the Coreflood botnet and sent code to the infected machines to disable the malware on them. The private security firm that did this first hijacked communication between the infected devices and the attacker's command servers. After collecting the IP addresses of the infected devices, they sent code to disable the botnet malware on them. Although the effect of this code on the devices was unknown, the action was ultimately successful and helped disable malware on over 700,000 devices in one week.

In November 2011, an FBI investigation brought down the Butterfly Botnet, which stole credit card and bank account information. It was comprised of over 11 million infected devices and resulted in over $850 million losses. Overall, 10 individuals were arrested from several countries.

In May 2014, the FBI arrested one of the co-developers of the malware Backshades, which was used to infect over 500,000 devices around the world. The FBI held over 100 interviews, 100 email and physical search warrants, and seized more than 1,900 domains used to control infected devices [Dem].

DDoS Botnets and Botnet Tools¶

Botnets are available from many different sources and are auctioned and traded by hackers. There are even online marketplaces for trading huge numbers of malware-infected computers. They can be rented and used for DDoS or various other attacks for a low cost, although the impact of these attacks can vary.

Analysis of a Mirai Botnet¶

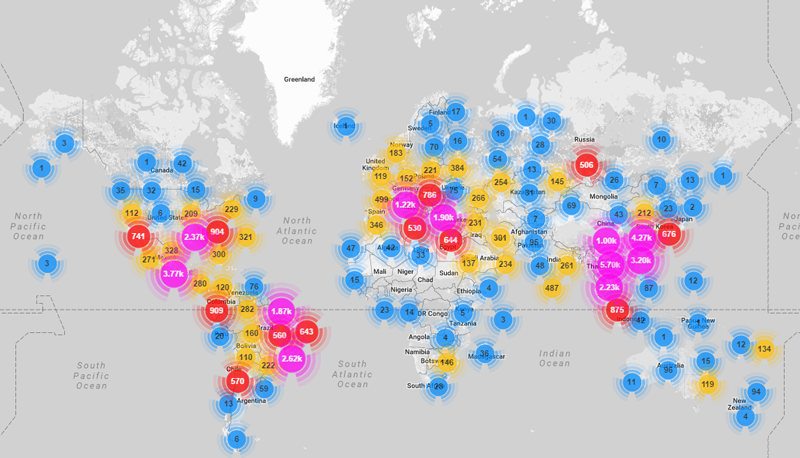

On September 20, 2016, the website of journalist Brian Krebs was subject to a very large DDoS attack. Like the attack on Dyn, the attacker used a Mirai botnet, mostly made up of hacked CCTV security cameras. An analysis by Ben Herzber, Dima Bekerman, and Igal Zeifman with their Mirai scanner found that the attack was made up of 49,657 unique IP addresses and devices in 164 different countries.

This image shows the locations of Mirai infected devices that made up the botnet [Bek].

Mirai attackers gained control of IoT devices mainly by guessing login credentials and gained access from default usernames and passwords still being used. The attacker gained control by using brute force based on the following list of credentials.

root xc3511

root vizxv

root admin

admin admin

root 888888

root xmhdipc

root default

root juantech

root 123456

root 54321

support support

root (none)

admin password

root root

root 12345

user user

admin (none)

root pass

admin admin1234

root 1111

admin smcadmin

admin 1111

root 666666

root password

root 1234

root klv123

Administrator admin

service service

supervisor supervisor

guest guest

guest 12345

guest 12345

admin1 password

administrator 1234

666666 666666

888888 888888 ...

One of the most interesting things they found while analyzing this attack was a list of hardcoded IP addresses the Mirai bots are programmed to avoid when performing IP scans. It include the U.S. Postal service, the Department of Defense, and the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority.

127.0.0.0/8 - Loopback

0.0.0.0/8 - Invalid address space

3.0.0.0/8 - General Electric (GE)

15.0.0.0/7 - Hewlett-Packard (HP)

56.0.0.0/8 - US Postal Service

10.0.0.0/8 - Internal network

192.168.0.0/16 - Internal network

172.16.0.0/14 - Internal network

100.64.0.0/10 - IANA NAT reserved

169.254.0.0/16 - IANA NAT reserved

198.18.0.0/15 - IANA Special use

224.*.*.*+ - Multicast

6.0.0.0/7 - Department of Defense

11.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

21.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

22.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

26.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

28.0.0.0/7 - Department of Defense

30.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

33.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

55.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

214.0.0.0/7 - Department of Defense

The botnet also holds several killer scripts to locate and eradicate other botnet processes from a device's memory. This is known as memory scraping. This behavior helped the attacker to maximize the potential of the botnet devices and prevent other malware from doing the same behavior to the devices [Bek].

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_QBOT // REPORT %S:%S

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_QBOT2 // HTTPFLOOD

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_QBOT3 // LOLNOGTFO

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_UPX // \X58\X4D\X4E\X4E\X43\X50\X46\X22

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_ZOLLARD // ZOLLARD

How to Build a Botnet¶

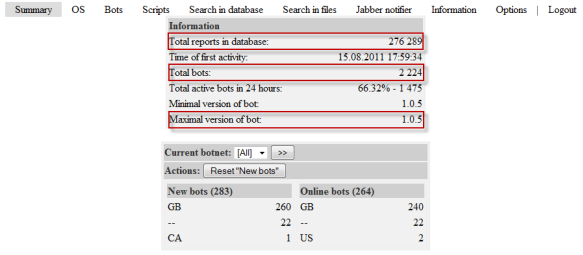

Another reason a DDoS attack is very threatening is due to the fact that setting up a botnet is fairly easy. Simon Mullis from FireEye simulated this process with a clean Windows virtual machine and a LAMP server on Amazon Web Service's EC2 platform.

These are the steps Mullis took:

- Downloading and installing the botnet builder tool for malware known as Ice IX

- Specifying parameters. For example, how often the malware would communicate with the command server, what actions it would take, and how it would hide from anti-virus scans. It can take screenshots of pages visited by the victim's machine, block sites such as anti-virus sites, and redirect legitimate URLS to malevolent sites to collect information.

- Encrypting and packing the infected file to install malware on the victim's machine

- At this point, the bot master can spread more malware to other computers [Pro]

This image depicts an early version of Ice IX Botnet [Mie].

Responding to an Attack¶

According to Akamai, an American content delivery network and cloud services provider, at the end of 2015, there was an 180% increase in the total number of DDoS attacks compared to 2014. Online gaming is the most susceptible to attacks, but software and technology companies still make up 25% of all DDoS attacks. [Rub]

Below are some indications of a DDoS attack taking place:

- Unusual network traffic could be the result of an attack. Performing network data analysis is important in understanding usual traffic flows.

- Unusually slow network performance

- Unavailability of website or inability to access site

- Increase in spam

If an attack is taking place, there are some steps a victim can take to mitigate the effect of the attack which include:

- Rate limit router to prevent web server from being overwhelmed

- Add filters to tell your router to drop packets from obvious sources of attack

- Timeout half-open connections

- Drop spoofed or malformed packages

- Set lower SYN, ICMP (Internet Control Message Protocol), and UDP drop thresholds

- Call ISP or hosting provider to stop traffic getting on the network

- Divert traffic to a scrubber to remove malicious packets [Rub]

How to Avoid DDoS Attacks¶

While there is no way to absolutely rid a company from the threat of a DDoS attack, there are measures the company can take to decrease the chance of a large, expensive and damaging attack from taking place.

- Architecture:

- Having a strong technical architecture can be important to decrease the risk of an attack

- Having servers in different data centers, locating data centers on different networks, ensuring data centers have diverse paths, and eliminating bottlenecks in data centers and networks they are connected to

- Hardware & Bandwidth:

- Network firewalls, web application firewalls, and load balancers can defend against protocol attacks and application attacks

- If it is affordable, it can be beneficial to scale up network bandwidth to absorb large traffic volume. This is more realistic for large organizations

- Outsourcing:

- There are also several services that specialize in responding to different kinds of attacks

- They can provide cloud scrubbing services for attack traffic

- Internet Service Providers can also offer DDoS mitigation that can help respond to attacks [Kar]

- Other:

- Having clear email distribution practices

- Applying email filters

- Creating proper authentication credentials for system administration

- Maintaining proper communication with customers

- Having a plan in preparation of an attack [Rub]

Distributed Denial of Service attacks vary in the effect they can have on a company or service, but they have the potential to cause a large amount of damage, especially when combined with other hacking methods. Although they are harder to stop and prevent than other denial of service attacks, there are ways that they can be mitigated and having a plan in place in preparation will also help.

Sources¶

| [Bek] | (1, 2) Dima Bekerman, Ben Herzberg, and Igal Zeifman. "Breaking Down Mirai: An IoT DDoS Botnet Analysis." Imperva Incapsula, 26 Oct. 2016 Web. 23 Feb. 2017. |

| [Dem] | Joseph Demarest. "Taking Down Botnets, A Statement Before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Crime and Terrorism." FBI News, 15 Jul. 2014 Web. 23 Feb. 2017. |

| [Dsa] | "Denial of a Service Attack." Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Web. 16 Feb. 2017. |

| [Hil] | Scott Hilton. "Dyn Analysis Summary of Friday October 21 Attack." Dyn, 26 Oct. 2016 Web. 20 Feb. 2017. |

| [Kar] | (1, 2) Rachel Kartch. "Distributed Denial of Service Attacks: Four Best Practices for Prevention and Response." Software Engineering Institute. Carnegie Mellon University, 21 Nov. 2016. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. |

| [Mie] | Jorge Mieres. "Ice IX, the First Crimeware Based on the Leaked ZeuS Sources." SecureList. AO Kasperksy Lab, 24 Aug. 2011. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. |

| [Pro] | Brian Proffitt. "How to Build a Botnet in 15 Minutes." ReadWrite, 31 Jul. 2013. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. |

| [Rou] | (1, 2) Margaret Rouse. "Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attack." TechTarget, Jan. 2017. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. |

| [Rub] | (1, 2, 3) Paul Rubens. "Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attack." eSecurity Planet. IT Business Edge, 25 Jan. 2016. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. |

| [Tho] | Karl Thomas. "Nine Bad Botnets and the Damage They Did." WeLiveSecurity. ESET, 25 Feb. 2015. Web. 21 Feb. 2017. |